Start right before you get eaten by the bear

How to avoid backstory scope creep

👋 Hey, it’s Wes. Welcome to my weekly newsletter where I share frameworks for becoming a sharper marketer, operator, and builder.

A lot of stories, presentations, and pitches take too long to get to the point. When I’m explaining a situation, I remind myself to “start right before you get eaten by the bear.” This means to cut non-essential backstory so you can spend time on the juicy part.

In this week’s newsletter, you’ll learn:

Part I: Aim for the minimum viable backstory

Part II: Good context vs useless context

Part III: Where to cut backstory

I originally published a version of this essay on August 8, 2019. Since then, hundreds of you have shared the post, so I’ve expanded the article with new insights and examples.

Read time: 10 minutes

Part I: Aim for the minimum viable backstory

I’ve been in 30 minute meetings where 25 minutes was spent on backstory. Long, winding explanation in the name of "giving context." I've been guilty of it myself.

Backstory scope creep is real. You start with the intent of sharing the only basics, but once you start talking, you keep going. Before you know it, you’ve explained the history of your product, covered your career journey, explained what you didn’t do and why, and went on a few tangents before catching yourself. Now there are only a few minutes left for your recipient to give you advice. You leave the call realizing you spoke the entire time, which negated the point of the call.

This is a losing situation for both sides: As the speaker, too much backstory means less time to receive advice and less time to focus on the real issues you wanted to discuss. As the listener, you zone out and get lost in irrelevant details.

So how do you avoid this?

By aiming for the minimum viable backstory. Ask yourself:

What’s the minimum backstory necessary to set the context, so we can spend time on the important stuff?

You’ll have to fight your urge to over-explain. You may think your audience needs to know all the details upfront. They don’t. You’d be surprised at how little backstory is needed to dive in. Once you start the conversation, you can always add relevant information later.

When you’re telling a story, it's even more important to remove backstory.

For example, I can tell you a story about how I went camping:

Three months ago, I started looking at national parks.

Researched car rental options.

Purchased a Patagonia half-zip pullover.

Drove five hours to the park.

Set up our tent.

Finally, 30 minutes in, I say, “And on the last night, Steve left beef jerky out. We heard rustling outside. The next thing we know, we’re almost getting mauled by a bear.”

WHAT?

Start your story right before you get eaten by the bear.

When you think there’s nothing left to cut, cut some more. It will feel painful, but you’ll be surprised by how much more efficient and impactful your words become.

Part II: Useful context vs useless backstory

Look, I see the irony in a long-form essay about avoiding backstory scope creep. At first glance, it sounds like the point is “keep it short.” That’s only partially true.

Avoiding backstory scope creep doesn’t mean to be concise at all costs. And concise doesn’t necessarily mean short. Concise simply means sharing enough to get your idea across with an economy of words. If everything had to be consumed in 30 seconds or less, the world would be a worse place for it.

To be clear, context is important. But non-essential backstory is different from useful context. I define backstory to mean irrelevant sidebars, rabbit holes, tangents, preamble, and background information that’s barely tied to your main point. If what you’re sharing is relevant and what you want to talk about, I don’t consider that backstory—that’s part of your actual story.

And it’s worth noting, if you’re a great storyteller, you can take as long as you need. Draw out the suspense. We want to hear the story for the sake of hearing the story. The problem is most of us aren’t great storytellers. And that’s okay. In business contexts, your listener doesn’t want or need a long story. The story is a means to an end to help your audience feel, to get them to take action, or to get your point across.

If you look at the structure of this article, you’ll see I put the most important part at the top. If you only read the top, you’d get the point. This was intentional. If you want to continue reading, you’ll see the framework fleshed out and explored in different ways.

Aim for as much as is necessary, as little as possible.

When we’re not sure what we want to say, we tend to get long-winded. This is because you’re thinking out loud—and it’s hard to think, analyze, and edit what you’re saying in real time. If you’re preparing for an important meeting, it’s worth spending 5-10 minutes to figure out what you really want to say in advance.

As a rule of thumb for myself, I aim for backstory to be roughly 10-20% of the conversation. This leaves 80-90% for what I actually wanted to talk about.

30 minute call: 5 minutes of initial backstory, 25 minutes for the real topic

60 minute call: 10 minutes of initial backstory, 50 minute for the real topic

Twenty percent of the call spent on backstory feels high, and ideally I could do 10%. But in practice, I’ve found it overly ambitious to do less than 5 minutes of backstory.

Once you start talking, it’s very likely your recipient will ask follow up questions. So really, you might spend more than 10 minutes on context, and that’s okay. The goal is simply to keep the initial backstory relatively contained.

You are not Faulkner. Stop with the exposition.

One reader said, “The Grapes of Wrath have chapters that are nothing more than description. No dialogue, just description, yet they are classic novels from award-winning authors. Would you have told them to delete these chapters?”

Here’s the thing: You are not Steinbeck, Faulkner, or Tolstoy. And your readers aren’t 11th graders with required reading. Your readers are coworkers, customers, sales leads, investors, direct reports, or your manager. They do not want to read anything remotely resembling Grapes of Wrath on a Monday morning.

You are writing to busy professionals with a lot on their plates, decisions to make, and information to process:

I’m using story loosely here—what I'm talking about are stories, explanations, and responses in a business context. In a work context, your explanation shouldn’t be a full 12 step Hero's Journey. No one has time for that, and more importantly, your story isn’t dramatic or interesting enough to be the Iliad. If you want to tell a story, make it a short one where a semi-distracted listener can get the point relatively quickly and feel the emotional pay-off.

You see this principle applied by storytellers who are much more skilled than you and me.

The Dark Knight movie opens with the Joker robbing a bank.

The Matrix opens with a police squad cornering Trinity, high-kicking agents in the face, then answering a ringing phone and vanishing.

Jurassic Park opens with zoo keepers attempting and failing to transport a velociraptor, which allowed room to explain the less exciting science that was crucial to the story.

Imagine the most recent TV show or movie you watched. Chances are, there was action within the first few minutes.

From reader and director Mitch Charman:

From a narrative perspective, starting with the moment before the highest point of tension is called a "cold open" (Law and Order style).

It came about as a result of there being so much noise, you need the promise of the premise upfront before audiences will trust you with their attention and emotions to take them back to the slow start of the ordinary world "once upon a time..."

Think Raiders of the Lost Ark, Indie escapes boulders and arrows and betrayal and snakes before we get a solid 20 mins of beige exposition at the university.

“Action” doesn't mean a Porsche has to blow up in the first 30 seconds on screen. It means giving the audience a reason to keep watching.

How this looks across mediums

Starting right before you get eaten by the bear applies to most situations at work, including Q&A, pitches, all-hands team meetings, 1:1 conversations, and sales calls. People want to hear the juicy part.

Answering a question from your boss

Make the best use of time by focusing on the punchline upfront. You will instantly seem more competent and organized.

Before: “This happened, then this other thing, and here’s the process of what I did for that, oh yeah this thing but that’s not important, this important thing that’s completely buried, and then this other thing.”

After: “Here’s 1-3 sentences of minimum viable backstory. Here’s the important thing I wanted to discuss…”

Asking for advice on a call

Some of the most successful people I know are insanely good at keeping backstory short, to the point where I’ve found myself thinking, “How were they able to say so much in so few words?”

If you’re asking for advice, it’s likely your situation has a non-obvious solution, multiple variables, or complexity involved—if it were easy, you would have solved it already. It’s possible your problem can’t be simplified any further. In many cases, though, there’s opportunity to challenge yourself to cut more backstory.

I’ve noticed the more experienced and sharp your conversation partner is, the more likely they can quickly pick up what you’re putting down. You don’t need to over-explain because they’ve either experienced the situation themselves or have seen this happen with others. In those cases, I like explicitly giving permission and encouraging folks to interrupt me once they get my point.

If you are an advice giver, you may want to ask upfront if the advice receiver would prefer for you to interrupt them. For example, I started saying this to my clients and have received positive feedback:

Slack messages

Put the key point at the top, then more context beneath. Here’s what this looks like:

And here’s a screenshot of a longer message because sometimes the context is necessary, especially if you’re making a business case and the decision has high stakes. In the example below, I shared what I was advocating for, then more on my thought process, rationale, potential risks, and logic.

Emails

I liked this example from reader Lucia Csoma:

I had to learn this [start right before getting eaten by the bear] when writing my emails. I use BLUF - Bottom Line Up Front. An effective BLUF needs to answer quickly the 5 W’s: Who, what, where, when, and why.

Before I learned about BLUF:

"Hi, Mike, based on our last discussion about the budget and at your recommendation Angela, Mike, John, and I had a meeting today at 9:15 AM to discuss the challenges we're facing in regard to the proposed budget."

After I started using BLUF:

"Hi Mike, we've updated the proposed budget and need your sign-off by 3 PM. This will help us present it during the board meeting. The background info is below. Let me know if we need to meet."

Only after a good BLUF, I would add all the background information. The background would have all the details I think Mike needs in order to approve the updates by 3 PM.

Presentations

“I wish the panelists spent more time talking about their backgrounds,” said no one ever. If you’ve attended a webinar, conference workshop, or keynote talk, you’ve likely seen speakers who spend too much time on the “About me” slide, which is the slide incarnation of too much backstory. The “About us” slide is the equivalent for an organization. Share just enough to establish credibility, then trim as much of the backstory as you can.

Articles

Here’s what Lenny Rachitsky said he from learned from building his Substack newsletter to 500,000 subscribers:

Before I started this newsletter, I’d never written anything publicly, taken writing courses, or studied writing. But after doing a bunch of writing, and reading three impactful books (On Writing Well, Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t, and Several Short Sentences About Writing), the biggest lesson I’ve learned is to cut, cut, and cut some more.

Cut every word that isn’t

absolutelynecessary. Make your intro 50% shorter. Get into the meat of your post as quickly as possible. As Wes Kao puts it, “Start your story right before you get eaten by the bear.”As an example, with almost every guest post that I edit, if I remove the first paragraph of the first draft, the post immediately gets stronger. Try this with your next piece of writing. Cut the intro and get right into it.

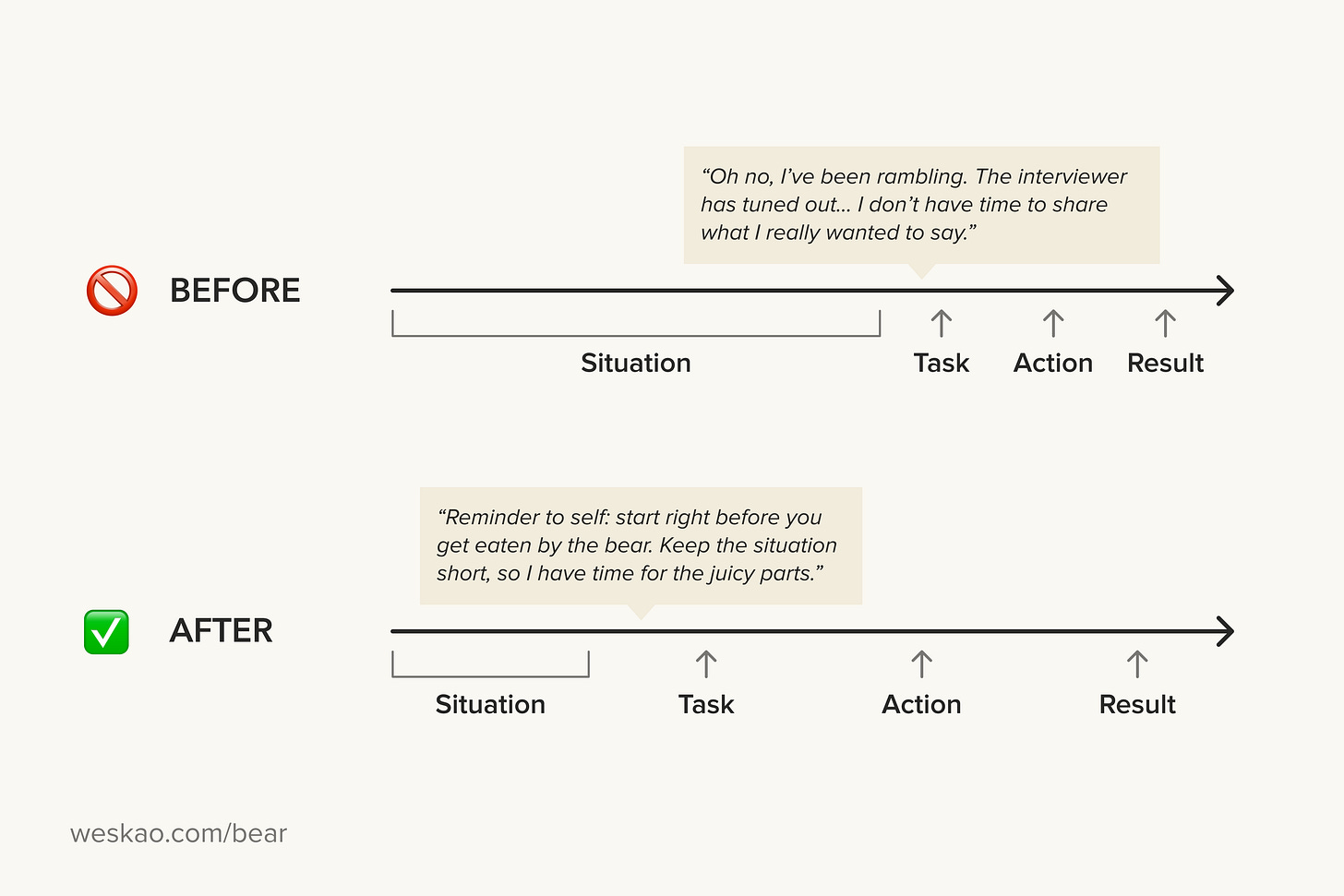

Job interviews

I’ve lost track of the times I’ve interviewed candidates, and gotten lost in at least one of their answers. These are usually high performers who made it through multiple other rounds before I met them. Succumbing to backstory scope creep isn’t a reflection of their ability—I see it as an expression of how pervasive backstory scope creep is and how it’s something we all have to be vigilant about.

For answering behavioral interview questions, the classic framework is the STAR method (situation, task, action, results). It’s easy to accidentally spend too much time on the situation part of STAR. Maybe it’s because you’re getting warmed up, or you think describing the situation is important for the rest to make sense. In either case, remember to allocate your time appropriately so you have time for the even more relevant and interesting parts, like pretty much every other part of STAR besides the situation.

Part III: Where to cut backstory

Here’s are places where folks are starting right before they get eaten by the bear.

In sales calls:

In podcasts, if you’re the host:

In podcasts, if you’re the guest:

If you’re asked to give a short summary of your career journey:

If you’re asked a high-intent, specific question:

At parties:

When telling a story:

When writing content:

When creating marketing videos:

In strategy write-ups:

Hosting a webinar:

When presenting to executives:

When presenting to prospective clients:

At networking events when you talk about yourself:

On customer service calls:

When explaining a concept:

When interviewing for jobs:

When explaining troubleshooting:

When teaching a live, cohort-based course:

When filling out applications and RFPs:

When you’re starting to give backstory on your backstory:

In meetings:

Takeaways: Trim as much backstory as possible because it’s usually not as important as you think. Non-essential backstory is different from useful context. Challenge yourself to remove tangents, random details, and rabbit holes. Start right before you get eaten by the bear.

When are you susceptible to sharing too much backstory? What’s an occasion this week where you’ll practice starting right before you get eaten by the bear? If you tried this, how did it go? Let me know in the comments.

If you found this valuable, consider subscribing if you haven’t already, or take a moment to refer a friend. When you refer friends, you’ll unlock referral rewards of my personal book lists and not-yet-published spiky points of view.

Thanks for being here,

Wes Kao

This was the backstory slap in the face I needed. Thank you!

I love this - and I find that when I want to go heavy into my back story - typically it's because I doubt my main point is strong enough to stand on its own. If I trust my idea and am primarily focused on providing value to my reader (rather than soothing my ego or making myself appear better/smarter) - this is much easier to do.