“What will I tell my boss?”: Why founders should understand the worldview of bureaucrats

A bureaucrat doesn’t care about good results, investing in a long-term solution, or the ROI of your product. They care about keeping their job and not getting in trouble.

👋 Hey, it’s Wes. Welcome to my weekly newsletter on managing up, career growth, and standing out as a high-performer. I originally published a version of this essay in August 2018. Enjoy.

Read time: 9 minutes

“This is the policy.”

When someone cites policy on you, it’s hard to push back. It’s a strong frame because the person uttering these four little words has the power of an entire organization behind them.

Who are you, a mere mortal, to challenge policy?

Never mind if the policy doesn’t make sense in your situation. Policy is policy.

When you’re a startup founder or forward-thinking leader trying to build something new, you need people to give you money, give you support, or give you their word not to block you. In your quest to sell your ideas, you might have to deal with a specific kind of person: a bureaucrat.

You might think bureaucrats only work at large organizations or at the DMV, but don’t be fooled. Bureaucrats come in all forms, and they’re hiding in plain sight ready to block you as much as they can.

So what can you do to increase your chances of success?

⛑️ Welcome and thanks for being here! If you’re looking for an external perspective from a former founder/operator, I typically work with tech leaders on: managing up to a CEO/SVP, strengthening your executive communication, and delegating to a team of ICs while raising the bar. If you’re interested in how I can support you, learn more about my coaching approach.

1. Start by understanding the bureaucrat’s psychographics and mindset.

Many bureaucrats have comfortable positions at established organizations. They don’t benefit from shaking things up. In fact, shaking things up might be the worst thing that could happen to them.

In 2024, you see every major auto manufacturer producing electric vehicles. But why weren’t the executives at Mercedes Benz, Ford, or General Motors panicking about electric vehicles 10 years ago? If you use the lens of a bureaucrat, it’s easy to see why they weren’t eager to take action back then, despite early signs that EVs would become the way of the future.

Where was the upside in embracing change for a bureaucrat? Back then, a VP at Audi who had a great salary and title simply needed to maintain the status quo. If they rocked the boat, there was little upside. They might retire within five years, so some new up-and-coming VP was going to get all the credit when their work came to fruition years later.

If the executive at Audi simply stayed the course, they could continue to reap the benefits of the status they had already earned. Why risk that for an idea that might not work?

You must remember: A bureaucrat doesn’t care about good results, investing in a long-term solution, or the ROI of your product. They care about keeping their job and not getting in trouble.

2. “New” could be the best or worst thing you tell someone.

Bureaucrats prioritize how defensible their actions are. What does this mean for you as a change agent?

First, try to avoid bureaucrats. It’s much easier to sell to someone with a worldview that matches yours. If your solution is new… look for someone who wants something new.

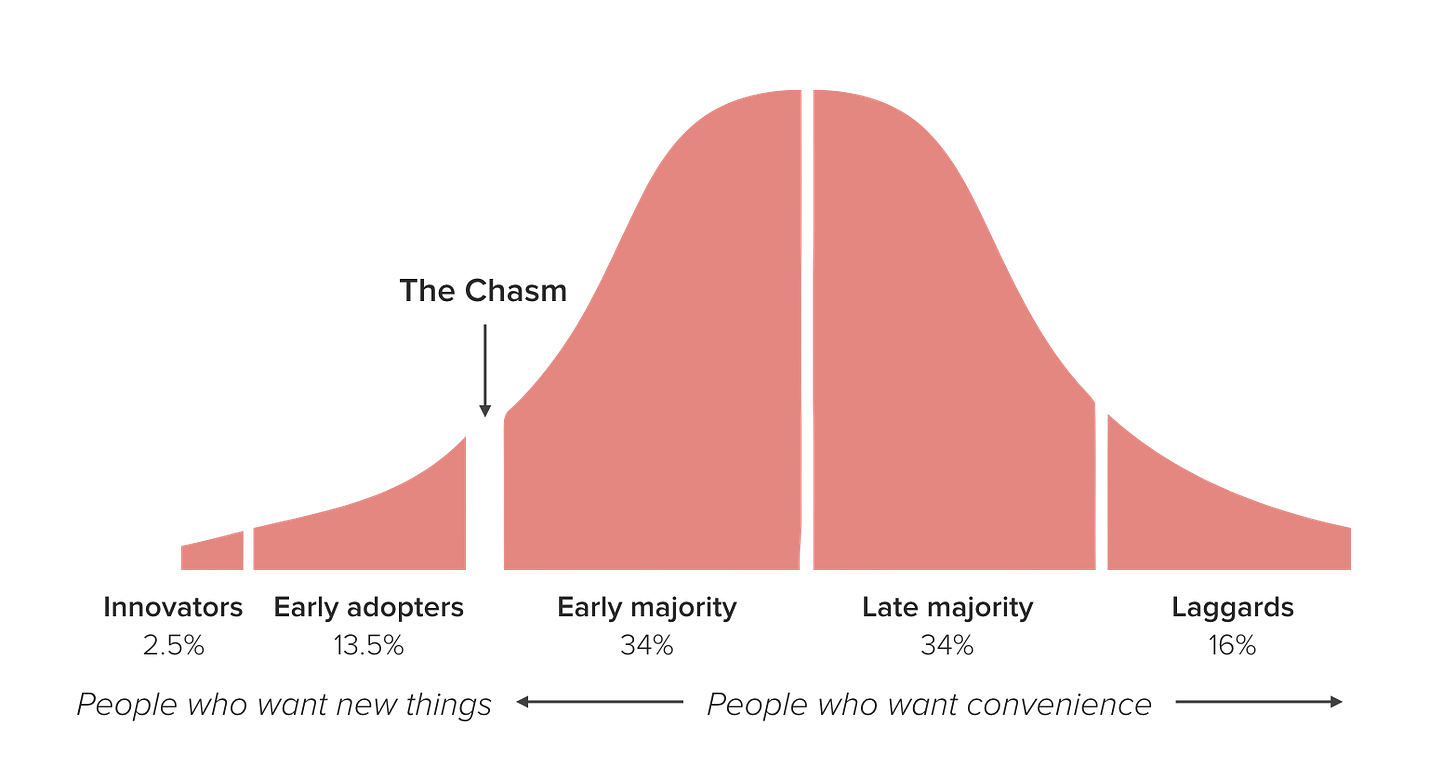

A bureaucrat is likely part of the early majority, late majority, or laggards. To them, anything cutting-edge is fraught with risk, unexpected errors, and mistakes waiting to happen.

The bureaucrat thinks, “Why should I be a guinea pig for your new idea? I’ll just have to clean up the mess when things go wrong.”

You can spend months trying to convince someone to embrace newness—but they’ve spent YEARS with this mindset. So asking them to change 180 degrees will be unlikely.

Be mindful of how much you play up newness when appealing to bureaucrats. It’s better to emphasize how safe, proven, reliable, and normal your product is.

We know that shaking things up threatens the bureaucrat’s sense of security and equilibrium. Just like newness feels dangerous, so do ideas that might be hard to explain to a superior.

Remember: There’s a big difference between wanting to be right, and wanting to avoid being wrong. This means they’re optimizing for having a foolproof answer when the boss asks, “Why did you (or didn’t you) do this?”

A common and satisfactory response for a bureaucrat would be: “This is the way we’ve always done it.”

Those are dreaded words for a founder to hear. But you have to admit, if a bureaucrat is optimizing for deniability, that response is pretty solid.

So how can you attempt to shift a bureaucrat’s frame?

3. Use social proof. Lots of it.

If you sell to bureaucrats, try to make your solution feel as safe as possible. How?

Social proof makes an idea feel safe because it shows that other people have already taken the leap. Related to social proof is the idea of precedent. Bureaucrats like precedent because it's essentially institutional social proof. If something has been done before within the organization or industry, it’s safer in a bureaucrat's eyes.

The bureaucrat does not want to be ostracized or laughed at for making the wrong move. They got this far by playing it safe. It would be foolish to let you, a random wahoo, ruin what they have going for them.

Proactively help the bureaucrat answer this question, “What will I tell my boss?” You can use this for non-bureaucrats, too. Re-framed, it’s this question: “What will I tell my friends, family, or coworkers?”

Here are examples of social proof, and what the bureaucrat thinks when they see it.

Investors: “VCs were willing to put cash money in them. This company must be up-and-coming.”

Press: “A famous magazine thought they were good enough to write about.”

Word of mouth: “A friend I trust is saying this is worthwhile.”

Halo effect: “She went to MIT. She must be legit.”

Good design: “Their website looks good. They must be a real company.”

Testimonials: “Other people like me have liked this.”

Advisory board: “These people were willing to lend their names and faces. This must be credible.”

Customers: “They have lots of other customers. X number of people can’t be wrong.”

4. Create a situation where it’s more dangerous to say no than to say yes.

Another strategy to appeal to bureaucrats is to make it better for them to say yes than to say no. In other words, if refusing you could put their job at risk, then they’ll have to say yes.

For example, let’s say you’re trying to get past a gatekeeper to get to the decision-maker. If you met the decision maker at an event and they told you to reach out, you’d want to mention that.

Why is this effective? Because the gatekeeper is now thinking they have two choices:

“If I don’t forward the note, and she really did meet my boss, my boss would be mad that I didn’t forward it. Might as well forward the email to be safe.”

“If I forward the note, and my boss knows her, that’s great. If my boss doesn’t know her, she’ll just ignore the note and it won’t take too much of her time. I should forward the note.”

In the situation above, it’s better for the gatekeeper to forward the note.

Notice that the gatekeeper didn’t forward your note because your product was better, you eloquently described your solution, or they realized your idea was great.

No, the gatekeeper simply made the mental calculation of, “How defensible is my decision? What will I tell my boss?” And they decided the most defensible (safest) thing to do was to forward your note.

A friend who works for the government said,

“People in government love cc’ing their manager, their manager’s manager, and other people's managers. They want you (their recipient) to feel pressure because more senior people are on the email thread. They want a paper trail to defend themselves and blame someone else in case a decision was the wrong one.”

They also said multiple coworkers print out every email they receive because they don’t like using technology. If the person you’re selling to thinks email is hard to get used to, think about how they’ll react to your new AI-driven B2B SaaS software solution.

5. Beware of faux early adopters.

Even people who say they love betting on bold ideas can secretly be bureaucrats in denial. You’ve probably met a number of senior leaders who claim to be risk-takers…

Only to disappear the moment you actually need them to take a risk.

These people are faux allies—you can’t depend on them to be internal champions. Make sure your internal champion is actually open-minded and willing to try something new. Otherwise, you’re wasting your time.

Being a bureaucrat is a mentality, not a title.

This is why supposedly forward-thinking functions can show risk-averse behavior. For example, venture capital. VCs love to act like they like taking risks, but many are quite risk-averse. That’s why getting your first investor is usually the hardest. If a respected investor is interested in you, other investors assume you must be worthy.

“What will I tell my boss?” That is the question a bureaucrat cares about. Whether subconsciously or consciously, that drives their worldview and behavior.

As a change agent, you have limited emotional bandwidth, time, and resources. You must proactively answer this question both verbally and non-verbally, explicitly and implicitly in your copy, images, and design.

6. Don’t judge others for being risk-averse.

Many of us love thinking of ourselves as early adopters.

Here’s the thing: You are probably not an early adopter in every aspect of your life and work. You might be an innovator in some areas of your life, but not others.

You might be an early adopter for tech gadgets, but a late majority for fashion. Or an early adopter in entertainment and music, but an early majority for food trends.

Roles aren’t static. They’re fluid and context-dependent. Sometimes you’re the change agent, sometimes you’re the gatekeeper, sometimes you’re the bureaucrat.

It’s okay, and there’s no judgment. It is useful, though, to know which role you’re playing and which your audience is playing.

Each of us decides what we feel is worth taking a risk for. If you see yourself as the kind of person who takes risks for ideas you believe in, make decisions that reflect that. Obviously, be smart about it—after all, you need to stick around long enough to shepherd your proposal from idea into reality.

Here’s to all the change agents working to make a difference. I hope these insights on how to appeal to bureaucrats can help you empathize with and influence different types of audiences you might encounter.

Have you experienced selling to or engaging with a bureaucrat? Hit reply because I’d love to hear from you.

Thanks for being here, and I’ll see you next Wednesday at 8am ET.

Wes

PS Here are more ways to connect:

Follow me on Twitter or LinkedIn for insights during the week (free).

Check my availability to do a keynote for your team.

Learn more about 1:1 executive coaching. My clients include director- and VP-level operators at companies funded by Sequoia, Accel, Kleiner Perkins, etc.

Sell your ideas, manage up, gain buy-in, and increase your impact in my 2-day intensive course. Students are operators from Uber, Meta, Netflix, Zillow, Square, Spotify, and more. This is the last cohort of 2024. Save your spot → Executive Communication & Influence for Senior ICs and Managers

"What will I tell my boss?"

I was listening to a podcast a while ago where the person being interviewed was talking about the sales process for people like this. He described the typical sales process of trying to appeal to FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) when you should be focussing on FOMU (Fear Of Mucking Up). "Nobody ever gets fired for choosing Microsoft"

Wes,

Right on the opening with "this is the policy", you made me think of, and then used as an example, a phrase that make some crawl up the wall:

"This is the way we’ve always done it.”

😡

Amazing piece as always. I really loved this line:

"Being a bureaucrat is a mentality, not a title."

I think knowing your audience is the main message here, then figuring out how to "present" to them.

Also reminded me of the 6 buying motives:

1) Desire for gain

2) Fear of loss

3) Comfort and convenience

4) Security and protection

5) Pride of ownership

6) Satisfaction of emotion

Our bureaucrat friends are squarely in #2 and #4, maybe even 3.

Preventing them from a Loss of their calm and peace, or strengthening their Security and Protection, are definitely the ways to go with them.

I just have to notice early on when I am talking with a bureaucrat mentality and change my tactic.

Thanks for the remainder.