Avoid incepting negative ideas

Ideas are fuzzy until you're able to put them into words, then they become concrete and real. Use this to your advantage to be more persuasive with customers.

👋 Hey, it’s Wes. Welcome to my weekly newsletter where I share frameworks for becoming a sharper marketer, founder, and builder, based on my experience as an a16z-backed founder.

This week, you’ll learn why you should frame ideas positively to guide your customer’s thinking in the direction you want to go. We’ll cover the following:

Part I: Don’t incept negative ideas

Part II: Examples of negative vs positive framing

Part III: How to reframe quickly

If you find it helpful, please share with friends and coworkers. Enjoy.

Read time: 11 minutes

Part I: Don’t incept negative ideas

If you speak about a thing, your audience notices that thing. This seems obvious, but I’m constantly surprised by how many marketers, salespeople, founders, and executives introduce negative ideas into their pitches and conversations.

Usually we introduce negative ideas to acknowledge customer concerns, seem more honest, or try to preempt objections. In my experience, you usually end up shooting yourself in the foot more than anything.

When a startup is pitching their product to a large potential customer, I often see founders who want to be upfront about how early-stage they are. They will open a pitch with something like, “We are only a team of 6 people right now, but we’re adding 5 new features to our platform every month and respond to all customer support emails within 24 hours.”

You think you are proactively setting expectations and preempting an objection, but there’s a good chance your prospective buyer got distracted when they heard “we are only a team of 6.” This set off alarm bells in their mind and they started questioning your ability to deliver on their needs.

The pitch above is stronger when you drop the caveat about your team size and open directly with positives: “We have a product that addresses your biggest pain point, and we’re adding 5 new features every month. On top of that, we respond to all customer support emails within 24 hours.” If you can handle their needs, who cares if you’re only 6 people? To be clear, I’m not saying to hide your team size. But you don’t have to lead with it.

The best example of incepting negative ideas was in 1973 when President Nixon said, “I’m not a crook!” during the Watergate scandal. Everyone seeing him on TV immediately thought, “Omg he’s a crook. I didn’t have the right words for this vague feeling, but now I do. You are totally a crook.”

Not only did Nixon incept the idea that he was complicit in wrongdoing, he gave America the language to describe his actions.

Scott Adams, the creator of Dilbert, calls this a “linguistic kill shot.” A kill shot is a phrase that’s visual, super sticky, memorable, and once you hear it, you can’t unsee it. There is usually some truth in a kill shot—just like customer criticisms of your product have some truth. This is why it’s so important not to give folks language to use against you. Don’t give them a kill shot to describe your company’s shortcomings.

Obviously, don’t be a crook. I’m assuming you’re a good person—which is why it’s even more important that you come across that way. If you’re a bad person and people think you’re bad, that’s fair. If you’re a good person but people think you’re bad because you incept negative ideas about yourself, that’s a shame.

Part II: Examples of negative vs positive framing

Because I’m an obsessive person who nerds out about messaging, I keep a running list of negative phrases I’ve heard people say over the years. Here are common situations where negative framing creeps in:

1. When a prospect doesn’t finish the sign-up process:

Before: “Looks like you were considering signing up for an account, but decided against it. I’d love to chat with you to answer any questions.”

After: “Looks like you were in the process of signing up for an account. I’d love to chat with you to answer any questions.”

As the customer, do you really want to remind me that I’ve already made this decision and said no? If anything, you want me to think I haven’t made the decision yet and there’s still room to decide to proceed.

2. When you tell customers you’re here to help:

Before: “We’re excited to invite you to join us. If you have any hesitations or questions, please reach out.”

After: “We’re excited to invite you to join us. If you have any questions or if there’s anything we can do to help, please reach out.”

When a customer first converts, they are not fully sold yet because they haven’t experienced the value you provide. They’re not really locked in, so you don't want them to think about hesitations. You want to reinforce why they made the right decision buying from you. The above example is simple, but the principle applies to more involved conversations too.

3. When a customer says they have concerns:

Before: “Hi Tom, thanks for being transparent with your concerns.”

After: “Hi Tom, thanks for sharing what's been on your mind.”

Concerns sound serious and negative, like something concrete you have to be overcome. Transparent can also be a heavy word because it’s typically used to preface dropping bad news. For example, when you see the phrase to be fully transparent, what follows is usually negative.

I’m intentionally assuming there's no obstacle—the person is simply sharing some news with me, and we can figure it out together.

4. When a customer says “not right now” but you still want to nurture them:

Before: “Hey, totally understand that now might not be the right time to teach. I'll have our head of partnerships reach out via email to share more.”

After: “Hey, totally hear you re: timing. I'll have our head of partnerships reach out via email to share more. This way you’ll have the info whenever you’re ready.”

First, the before isn’t logical because you understand that now might be the right time, but in the same breath, you say your colleague will follow up. It sounds like you weren’t listening.

Second, don’t repeat non-advantageous ideas. As anyone who’s tried to sell anything knows, when prospects say a generic excuse like I’m too busy, it doesn’t mean they’re too busy. It means you haven’t demonstrated how the juice is worth the squeeze. There’s always time and budget—for products that are deemed urgent and important. Therefore, in the after, I say timing because it’s a more vague term that acknowledges what the customer said, but also works for my colleague to reach out.

5. Manager giving their direct report some hard news:

Before: “I don’t say this to discourage you and be a jerk, I’m trying to empower you by sharing that…”

After: “I’m sharing this because [sell why the idea benefits your direct report]”

The second-person “you” is too on-the-nose. When you say, “I’m not trying to discourage you,” I literally think you’re trying to discourage me. I didn’t think that until you mentioned it, but now I almost don’t even hear the rest of what you’re saying because everything is clouded through this lens.

And then the “I’m trying to empower you” sounds like a cheap trick that insults my intelligence. I’m being hyperbolic on purpose, but I’m sure you’ve had conversations with your manager that felt a bit patronizing but didn’t need to.

There are a few technical reasons why the after version feels better. First, it’s a bit less aggressive because it avoids saying “you.” Second, the often-cited 1978 experiment by Harvard professor Ellen Langer showed that because is a persuasive word regardless of what comes after. I still recommend sharing a logical reason you actually believe in though.

Obviously, the context and the messenger matters. If a trustworthy manager you have a great relationship with said “I’m not trying to discourage you” and they seemed sincere, it’s totally fine. I’ve said this and have had people say it to me. I’m not saying you should never utter these words.

I’m saying, if the topic you’re talking about is negative to begin and you tend to stack other negative frames, then be mindful of whether you might be making a situation more tense than it needs to be. As always, use your judgment.

6. Leader giving feedback and the recipient not taking it well:

Before: “I’m not trying to accuse or attack. I want to...”

After: “I want to…”

Now that you mention it, you do sound like you’re attacking and accusing me…

7. Gut-checking with your team member about a deadline:

Before: “What do you think about March 1? Is that too aggressive?”

After: “What do you think about March 1? Is that doable?

This one depends on whether you hope the person will accept vs disagree. If you want them to say yes, saying doable gets them thinking about how it can be done. If you want to encourage them to push back, plant the idea of it potentially being too aggressive of a deadline.

8. Asking for answers:

Before: “I think it's not unreasonable to get an answer to at least one of these questions.”

After: “I think it's reasonable to get an answer to at least one of these questions.”

If you think your requests are reasonable, say reasonable. Otherwise, when you say unreasonable, the other person instinctively starts thinking of why you are being unreasonable.

9. Hiring manager negotiating an offer with a candidate:

Before: “I’m not trying to lowball your offer or get you for cheap. The way we came up with the offer was by looking at Carta comp data for…”

After: “The way we came up with the offer was by looking at Carta comp data for…”

You really want to avoid loaded words like lowball or cheap when talking to candidates. Many candidates are already afraid of being lowballed, so your mentioning this feeds into their fear. The negating word not isn’t strong enough to remove the visual from their minds. So don’t plant that visual in the first place.

10. CEO to their co-founder:

Before: “I won’t put your needs and wants in second place.”

After: “I’ll put your needs and wants on the same level as my own.”

Your co-founder is probably already worried they are in second place, and in many ways, they are. When you say it out loud, it makes the worry more real because now they know you are thinking about a ranking, and they are obviously below you.

11. New hire meeting their team on the first day:

Before: “I hope I won’t disappoint.”

After: “I’ll do my best.”

Starting off talking about disappointing your new team is negative for no reason. There are other ways to show you are humble.

12. Two executives arguing:

Before: “I’m not your enemy.”

After: “We are in this together.” “We are on the same team.” “I want to figure this out together.

I didn’t think you were my enemy, but now that you mention it…

You don’t have enough levers to treat words as throwaway

These are all things I have heard well-paid ICs, managers, leaders, and CEOs at tech startups say over the years. This includes clients who have raised millions in funding. So this is not merely an area that junior people can improve on.

And again, any one of these misses isn’t terrible, but when stacked, they really start to compound. Some situations are higher stakes than others. For example, in a compensation negotiation, you don’t want to introduce a word like lowball or cheap, even if you’re negating it. Those words are too loaded, and give the candidates something to latch onto and position your offer under. I’ve seen hiring managers need to increase their offer because candidates pushed back hard, thinking they were being lowballed when the original offer was within the 50-75% percentile mark of companies of that size, geography, and level.

It’s not “just” about words. Words shape how your recipient thinks and can either build or destroy goodwill, and save or cost you money. It can also be the difference between whether people trust you, are excited to work hard for you, and feel like you believe in them—or feel like you’re kind of an asshole.

If being mindful of your messaging took a lot of effort, I’d say, maybe it’s not worth it. But it takes very little effort, prevents misunderstandings you might have to spend hours/days addressing later on, and makes you someone people like and trust. It’s high ROI.

Part III: How to reframe quickly

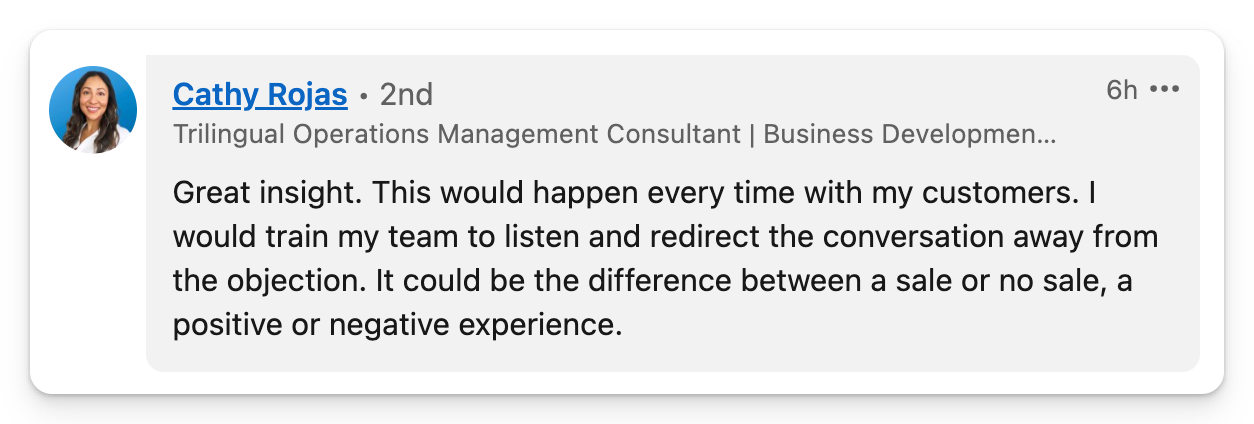

Most people spend too much time discussing objections, which means you're playing in the customer’s frame. Instead, you should show you were listening, then spend the majority of time painting a picture of the upside, derisking the downside, giving them reasons to say yes, etc. Remember: Your customer doesn’t necessarily know best. You might have context, examples, data, stats, etc that would help them come to your conclusion.

“But Wes,” you say, “How do I show I was listening if I can’t repeat the customer’s objections?” You can summarize, but try not to aggrandize, make it emotionally heavy, or inadvertently make the obection a bigger deal. Here’s what you can say:

“Yes I definitely see what you’re saying, which totally make sense and I’d think the same too. Another thing to think about, though, is [reframe or share a new piece of information that will help them see differently].

Once you redirect, continue with the new frame. A common mistake is to circle back to what the person said, but don’t undo your hard work by re-incepting that idea. You’ve moved on, so keep driving the conversation in the direction you want to go.

For example, here’s what I might say if a customer (instructor) mentions how it’s a lot of work to build a course at Maven.

Before: “I hear you. You might have spent nights after work, weekends, all your free time and time away from your kids working on this course, and to only have so few students must have felt surprising, disappointing, demoralizing, and like a complete waste of time. So I can see why you’re questioning why to do this. [Start to reframe].”

After: “I hear you. Building a course definitely takes effort and [start to reframe] I think the part that can feel hard is that most of the work is upfront. You build the course as an asset, then you can use that asset for the next 20 cohorts without changing it much or at all. But I agree, it’s definitely an upfront investment to get going.”

Do you see how the before version was too real? It painted a picture in the prospect’s mind that made their objection feel viscerally negative. In the after version, I started to reframe much sooner and didn’t trigger a visceral reaction.

In general, if I’m confident the customer is a good fit but they just don’t know it yet, I recommend spending 80–90% probing for what would make this exciting for them, sharing relevant context, and tying it back to their needs. Otherwise, you're not in control, you're simply reacting and getting pulled in random directions.

Like many things, a single isolated instance probably won't make a difference, but all those tiny missed opportunities compound and impact your ability to get what you’re aiming for. And the opposite is true: When you become attuned to opportunities to use messaging strategically, these are all “found levers” like “found money,” i.e. it’s a gift you didn’t realize existed until now, and it’s all upside.

Takeaways:

Don’t give people vocabulary to use against you.

Ideas are fuzzy until you're able to put them into words. If you want an idea to become concrete, verbalize it and spend time talking about it.

If you want an idea to remain in the background, avoid giving it air time.

Always incept positive ideas.

I’d love to get your help growing our community of thoughtful, rigorous operators. If you enjoyed this post, consider taking a moment to:

Refer a friend to unlock my non-obvious book recommendations for free.

Sponsor this newsletter to reach 27,000+ tech operators and leaders.

Thanks for being here,

Wes Kao

PS See you next Wednesday at 8am ET. If you’re loving this, check out my other essays on framing and strategic messaging:

I agree with a lot of this - one thing I'd add though is there are studies out there which show when you admit something you're not good at, you seem more trustworthy for things you claim to be good at. For example, in the sales process - acknowledging a small weakness helps increase credibility of the major claims. There's always a bit of a danger I think of trying to appear flawless.

This goes well with your article on skipping straight to the part where the bear eats you. I struggle with this compulsion to provide context before getting into the meat of the story or presentation. Again, a good reminder to cut out the unnecessary information at the beginning.