Are your standards too low? In defense of raising the bar

For every team that says “this is as good as it’s going to get,” there’s a doppelgänger team out there who refuses to settle. They are pushing & they will eat your lunch—unless you raise your bar.

👋 Hey, it’s Wes. Welcome to my weekly newsletter on managing up, leading teams, and standing out as a high performer. For more, check out my intensive course on Executive Communication & Influence.

⛑️ One of the most common areas I coach tech executives on is raising the bar for their teams. By working with me, you’ll get an objective gut check of whether you’re too hard or too soft on your team (many leaders are too soft IMO), where you can push them (and how to do it productively), and more. If you’re interested in how I can support you, learn more about my coaching approach.

In this week’s newsletter, I want to talk about why you should consider raising your standards and why this has the potential to dramatically improve your team’s chances of getting what you want.

Part I: Why every leader should set higher standards

Part II: Challenges when raising the bar

Part III: How to normalize a culture of excellence

Read time: 13 minutes

Over the years, I’ve been told by co-founders, direct reports, and peers that I raise the bar of quality in everything we do. Setting a high bar—and holding teams to this standard—is one of my strengths.

I’ve heard from leaders and managers who want to set a higher bar in their own organizations, but aren’t sure how to start. Many are afraid to upset team members who are used to operating a certain way. In this post, I’ll attempt to make the case for why you should set a higher bar for yourself and your team.

First, why raise your standards?

Part I: Why to raise your high standards

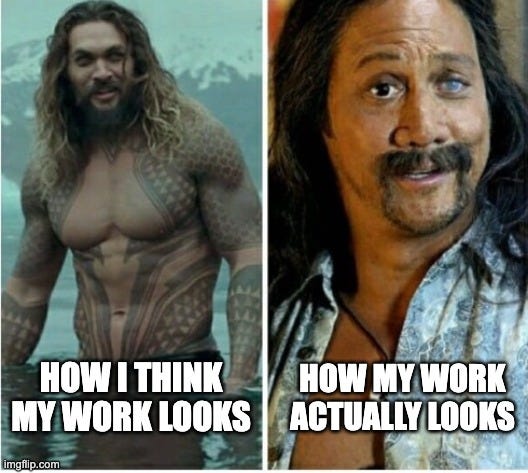

A tale of two teams: One with high standards, and one that scoffs at the idea that their standards may be too low

For every team that says “This is as good as it’s going to get,” there’s a doppelgänger team out there who refuses to settle:

This team isn’t just ticking off boxes. They are innovating, challenging assumptions, and pushing the limits of their creativity.

They are always scanning for inspiration and keeping an ear to the ground for what customers want.

They realize they don’t have many levers, and can’t afford to cavalierly pull levers in a half-assed way.

They know there’s a spectrum of quality for any attempt. They know there’s no upper bound for how strong you can be at any skill where there’s craft and judgment involved, including writing, coding, design, sales, etc.

They acknowledge that aiming for a high bar can feel challenging in the moment, but being great at your job is rewarding and fun.

This team knows what excellence is and aims for it, sometimes hits it, and often acknowledges the gap between their vision vs their skill.

The second team doesn’t even realize they have low standards:

This team makes a half-assed attempt, then claims, “This channel (THE ENTIRE CHANNEL) doesn’t work.”

This team uses lazy excuses like “there’s a speed vs quality trade-off!” when they are not remotely close to moving fast enough or shipping work that’s high quality enough to breach that boundary.

This team leaves money on the table, every week, and with every project, because they make dozens of mediocre micro-decisions when executing.

They default to knee-jerk reactions like “if we set bigger goals, we need to hire more people” instead of realizing that a lean team of the right people can be just as effective.

They cite popular aphorisms like “perfect is the enemy of good” to justify subpar work, instead of admitting there’s room to improve their execution.

They do okay work, at an okay speed, but feel like they’re sprinting and producing A+ work. When you challenge them, they are insulted.

There is a disconnect: They think they are producing high-quality work, but objectively, it’s simply passable. And therein lies the problem:

Their standards are too low.

The benefits of having higher standards

As a founder or leader, your team’s standards will be as high as your expectations are. You set the bar for what’s acceptable and celebrated. In other words, your standards are the maximum of what folks on your team will deliver. In my opinion, this alone is a compelling case for why you should at least consider raising your standards.

If you’re an individual contributor, you have the opportunity to raise the bar too. I believe we all have the chance to give detailed feedback, rooted in logic, to sharpen each other’s work and therefore collectively become stronger as a team.

You could keep doing what you’re already doing, and NOT raise your standards. But if you do, you’ll reap the rewards, of which there are many:

Leverage. When you change your team’s culture, you are creating a rising tide that lifts all the boats (i.e. team members) in the water.

Reduce decision fatigue: Stop being the only one who catches stuff that slips through the cracks and being the only one who makes decisions.

Produce better work output and outcomes: Eventually, you’ll spend less time giving feedback. (In the short run, you’ll need to give more feedback, which we’ll discuss later.)

Maximize your chances of winning. If you feel you have a chance at winning in a growing market, and are well-positioned to do so, then your ability to execute is the difference between failing and winning.

Motivate team members. High performers like working with other high performers. Having higher performers on your team attracts better talent.

Another reason why high standards matters: As a leader, you can’t see everything every person does every day. Managers, by definition, have less visibility into what each direct report is working on than the direct report does. You need your team to hold themselves to a high standard in the moments when no one is looking (which is most of the moments).

Part II: Challenges when raising the bar

Most people think they have high standards

You might be wondering, What if my standards are high enough already? How do I know if my standards are too low?

This is tricky because raising standards might look different for everyone. Some variables include your function, starting point, task-relevant maturity, skill level, and accuracy in assessing your own work. But I believe one thing: simply deciding to raise your standards is a big step.

When you decide to notice work that’s high quality, you will start to see examples everywhere that you can learn from and apply to your work. This is because when you decide to do a thing, your subconscious becomes more attuned to noticing things related to it. You can start to save screenshots, snippets, examples, make mental notes, etc of folks who do work that surprises and delights you. I see examples of people who do high-quality work everywhere, and it’s an endless opportunity to raise the bar for myself and further hone my ability to recognize quality.

One other thing to mention: defensiveness. Defensiveness is a natural reaction when confronting that your bar might be too low in certain areas, but it doesn’t have to be your response. It takes humility to admit that your expectations might not be high enough. Only once you do that, can you notice and learn from people who may have a higher bar than you. Simply choosing not to be defensive automatically puts you in the top quartile of folks who are likely to raise their standards.

When people get feedback that hints that their standards are too low, they often think, Oh, that thing you gave me feedback on is nitpicking. It’s unimportant. It’s over-optimizing. I intentionally didn’t do [x better thing] because I prioritized speed and shipping.

In reality, the truth is: I didn’t do [x better thing] because I didn’t think of it. I didn’t realize that a better way was possible. I wouldn’t have realized it unless you had pointed it out. Actually, I could have done this more elegant solution relatively quickly if I had identified it, but I don’t want to admit I didn’t see it as an option at the time.

Intellectual honesty is paramount. If a more elegant solution didn’t cross your mind, that’s okay. That’s a normal part of learning and improving. The part that’s not great? Pretending that feedback isn’t valid simply because your psyche feels threatened.

Ask yourself:

When might you be brushing off legitimate feedback to protect your ego?

If, instead, you accepted the feedback and looked for truth in it, you might realize you can move just as quickly AND achieve higher quality. Or you might be able to achieve the “both/and” of what you initially thought were at odds.

Common excuses to avoid raising the bar

“It’s good enough.” This is tough because people have different standards for what bad vs good vs great looks like. What’s good enough for one team might be too low quality for another. For example, some people think their copy or design is strong, but I’ll think it’s barely passable. I’ve had colleagues on hiring committees rank candidates a 9/10 but I gave the same candidate a 4/10. In general, I agree aiming for good enough is useful, except when it’s an excuse to be mediocre. It’s like saying a product is a minimum viable product (MVP) when it’s minimum, but it’s not viable.

“There’s a trade-off between speed and quality.” You likely have plenty of room to do both before needing to make this trade-off. Chances are, you’re not remotely close to that edge. For example, when I moved to New York to work with Seth Godin, I had come from a series D startup in San Francisco backed by Sequoia Capital. I thought I knew what shipping fast meant—I did not. I had no clue. Seth Godin set a bar easily 10x higher than what I was used to. The wild thing is I wouldn’t have been able to imagine that this speed or quality was possible until I was pushed to do it. So instead of insisting “it’s not possible,” think about how you can get creative with scope or reframe the problem. In the long-term, invest in sharpening your craft to become more effective and efficient.

“It’s optimizing past the point of diminishing returns.” Obviously, stop before you hit the point of diminishing returns. The problem is people stop way before reaching the point of diminishing returns but claim they’ve hit diminishing returns.

“It’s too much work”: Raising the bar isn’t necessarily more work. It’s often about improving your intuition, decision-making accuracy, exposure to what’s possible, and taste level, so you’re making better judgment calls. For example, an experienced marketer can instantly point out areas to improve that others don’t or can’t see. These folks had more exposure and data points on what quality looks like, and then over time, they worked to hone their craft. So yes, it requires effort to hone your craft, but eventually it might mean less work because you’re more effective at translating your intent into reality. To be clear, sometimes raising the bar does require brute force and spending more time on a task, but in my experience, it’s not the main driver.

“Done is better than perfect.” Like all things, it depends. If you make a sloppy attempt, is done really better? Doing excellent work will take longer. But I’d argue that a careless job is slower because (a) it won’t get you to your goal, (b) it won’t be well-received by your leads or customers, (c) it won’t instill trust in your brand, so (d) you’re going to have to redo or (e) keep burning through new tactics.

“It’s not worth the ROI to make it better.” Some things might not be, but some things are worth it. Use your judgment. Don’t use this as an excuse to be lazy because you’re tired of solving a hard problem that isn’t bending to your will, and you’d rather move on to a fresh project.

“Quality is hard to define and varies by function, project, etc.” You and your team get to define what quality means to you. Sure, quality could mean different things—that’s not an excuse to avoid doing quality work though.

Part III: Normalize a culture of excellence

Aim for a culture of high standards, high feedback

I believe one of the best ways to raise your standards as an organization is to aim for a culture of high standards and high feedback. You need both. You can’t simply proclaim, “we’re raising our standards now” and expect everyone to know what’s expected of them.

Just saying it doesn’t do anything—you must create a new norm. I like this quote from Andy Grove, co-founder and former CEO of Intel:

"Values and behavioral norms are simply not transmitted easily by talk or memo, but are conveyed very effectively by doing and doing visibly."

Creating a new norm involves reinforcing the new standard every week, across every team, across different situations and conversations, in private and public, in big and small moments. This is how team members come to understand what a higher standard means in your organization.

Here’s a 2×2 matrix of standards vs feedback:

Organizations with high expectations, paired with a high degree of coaching, are the most rewarding for both the organization and individuals.

High standards, low feedback: sink or swim

High standards, high feedback: holy grail

Low standards, low feedback: most companies are like this

Low standards, high feedback: unsustainable and poor ROI

Some companies can get away with a sink or swim culture because they’re clear upfront about their expectations and they attract ambitious masochists. For example, McKinsey is known for 100-hour weeks. At GE, Jack Welsh famously fired the bottom 10%. People self-select to work in extreme environments like that.

The people who chose to work at your company, well, aren’t at McKinsey and GE because they’re working for you. And you probably haven’t had high enough standards until now. So if you want to shift your culture to be more hardcore, you need to provide support and give people a chance to see how they like this new environment.

Who will come along for your new high-standard environment? People will fall into three buckets:

No: These team members say, “No way. This isn’t what I signed up for.” They will grumble or revolt, and eventually leave.

Yes: There might be team members who were always hardcore inside. They’ll be happy everyone else is finally embracing higher standards.

Maybe: These “swing states” are team members who could go either way.

The “swing states” are people who COULD be excellent but are deciding whether they want to rise to the occasion with you. These individuals are sharp and motivated enough to be excellent, but also savvy enough to cruise if they choose to. Depending on the breakdown of people in your organization, the swing states could be your fulcrum.

This is where setting your culture and explaining the logic behind your culture is crucial. I think logic is underrated in most conversations. Most people think repeating a high-level, inspiring vision is enough, but actually, people need shit to make sense. So you need to say, “Hey, here’s what we do when something like this happens” AND “Here’s why we do it like this, and why it benefits you and the company.”

Why to give detailed feedback on work output

A major lever for raising the bar is giving your team members actionable feedback on work output on a regular basis. Unfortunately, when team members run their work by their managers, many managers are on one end of this spectrum:

(A) Takes a quick look and says “looks good” regardless of whether it looks good

(B) Recognizes the work isn’t good, but makes all the changes themselves because it takes too long to give feedback

I’ve been in both of these positions myself, and sometimes, it makes sense to let mediocre work slide or to do the work yourself. But I find many managers will act reflexively, and therefore lose opportunities to coach their teams, because they tell themselves the narrative that “I’m prioritizing shipping and moving quickly.”

The problem with this logic is very few pieces of work output will ever seem that important in isolation. When no individual piece of work is important enough to give feedback on, you never give detailed feedback on work output. The result: your team members never learn.

They never learn what excellence looks like because whatever they sent you, you said it looked good. Obviously, there are tasks that are low ROI. But there are absolutely projects and sub-parts of projects that are more highly leveraged. Once you stack rank and decide that X is worth the effort, you should execute well on X.

For example, the pitch DM your junior team member is using. It might seem small—it’s “just” a DM, right? But if it’s getting sent to hundreds of leads per week, and is the first touchpoint between a lead and your brand, you can’t afford not to optimize the conversion. The way your team member answered a question from the high profile customer—it’s “just” an email, right? That email could cost you a six-figure deal because the team member’s answer didn’t address the customer’s concerns or sell them on why to continue using your platform.

You might be thinking, “I don’t know if taking the time to give feedback on this piece of work is worth it.” In the grand scheme, does this email matter? This particular email? No.

But your employee’s ability to write persuasive copy, think clearly, and position ideas? Yes. That absolutely matters.

This is how individuals improve: One step at a time. One piece of work and one conversation at a time. If you refuse to have those conversations with your team, you can’t expect them to improve. (More on how I give Super Specific Feedback on work output, such as writing, product flows, marketing assets, and design.)

Don’t let things slide, i.e. don’t let folks get away with bad behavior

Yes to accountability, but how? Let’s narrow in on the team level because most leaders have more direct influence over their team. And if every leader did this with their teams, it would roll up to a company-wide culture of accountability.

I think the way you create accountability is to ”not let things slide.”

Here’s what usually happens:

Your direct report turns in work that’s mediocre.

You try to convince yourself it doesn’t bother you because you’d rather avoid figuring out how to give uncomfortable feedback.

You decide to let it slide.

Your direct report continues to do the thing. You hope they change.

Surprise: They don’t change. This is now your new dynamic.

Here’s how it could be:

Your direct report turns in work that’s mediocre.

You point out why their work was only decent, give actionable feedback on what to do differently, and explain why this new approach is better.

They realize they can’t “get away with” subpar thinking because you will lovingly call them out.

People have agency. If they don’t like the culture and expectations, they don’t have to work with you. The world is a big place—there are hundreds of thousands of employers out there. I owe you being clear about what I expect, setting a high bar, and offering support and feedback along the way. You get to decide if that’s something you find motivating, rare, and a career-changing environment. Or you can opt out. Either works.

Working on a team with high standards will sharpen you more than any course, book, mentorship, or formal learning opportunity will. It will change you as a person. You will not be able to unsee nuance, and excellence can become your default.

If you are lucky enough to be on a team with a high bar, I recommend maximizing your time learning on this team. One thing to note: Raising your standards is fulfilling and potentially career-changing, but by definition, higher standards mean that lower-quality thinking or lower-quality work doesn’t fly.

This means you have to be open to doing things differently than how you did them before. In the short term, these changes might feel painful or jarring. But soon, you’ll find that iron sharpens iron—and there’s a certain thrill from working on a team that cares about excellence.

Is it worth it? That’s up to you to decide. You can help set higher standards in your organization, no matter who you are, regardless of your title. You can be the one who says, hey, I think we should raise the bar.

Takeaways:

Teams who have high vs low standards behave differently.

You can’t simply proclaim, “we’re raising our standards now” and expect everyone to know what that means. You must create a new norm.

There are many benefits of having higher expectations, including motivating your team. High performers like working with other high performers.

There are common reasons to avoid raising the bar, but most are excuses.

In the 2×2 matrix, aim for high standards and high feedback.

Give actionable, detailed feedback on work output so your team has an opportunity to learn and improve with every project they do.

I’d love to get your help growing our community of thoughtful, rigorous operators. If you enjoyed this post, consider taking a moment to refer a friend to unlock my book lists and not-yet-published spiky points of view.

Thanks for being here,

Wes Kao

PS See you next Wednesday at 8am ET.

PPS More articles on how to give feedback to raise your team’s standards:

I'm consistently blown away with how broadly applicable these posts are. Working as an engineer, every one of these points hits home just the same as if I were in marketing. Truly impressive

What would you say to a direct report whose manager does have a culture of high standards but is also low on actionable feedback? What kind of steps can the direct report take at that point?